“All his life, he thought he wanted to know the face of the woman who had given birth to him, but a single picture, a name -- it would be too much. It was the not knowing that protected him, the blank page that allowed him to believe she might be anyone, or might not exist at all. He could have been raised by wolves. He could be the son of God or a test tube miracle or for all he knew he could have fallen to Earth with the snow from the sky.”

“Even when the baby was out of her ... she kept her eyes closed tight. She knew how easy it is to fall in love.”

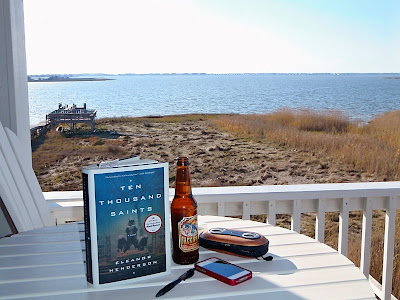

Though it had a couple of holes, Eleanor Henderson’s fascinating look at 1980s New York and the straight edge movement made “Ten Thousand Saints” a haunting, compelling read.

Early on, Henderson centers in Vermont, on Teddy, who dies of an overdose early on (“No foul play had taken place, just an accumulation of poor choices.”), and Jude, Teddy’s best friend and a rampant drug user (“He was good at nothing if not faking sobriety.”). Later, we are introduced to Johnny, Teddy’s stepbrother and underground tattoo artist/rock star in New York City; Eliza, Jude’s sort-of stepsister and a 16-year-old coke abuser who becomes pregnant with Teddy's child after a one-minute stand (“Now Teddy and Jude had left her to fend for herself, and she was fending. She was a girl who knew how to fend.” ); and Les, Jude’s separated stepfather who is dating Jude’s mother. Needless to say, there are a lot of dots to be connected here and a lot of pieces to puzzle out.

“They liked to conceive of their situations in terms they were familiar with. Punk bands, musicals, young adult movies. Jude and Johnny were the Greasers fleeing the Socs, and Eliza was Cherry Valance, the girl from the right side of the tracks. They were the Runaways, betrayed by their parents, only they’d stitched their way into and out of so many states it was hard to keep track of which one they were running from.”

According to Henderson, the story was inspired by her husband’s experiences in the New York of the late 1980s. Like many readers I’m sure, I had to question the inherent difficulties in a woman writing about the issues facing a series of teenage boys a quarter of a century ago (not to mention that Eleanor Henderson is a certified old-lady name). However, she did an admirable job interweaving the characters’ backgrounds into the story, and even though it felt forced in some ways, it is an admittedly difficult balance to achieve.

The tale also jumps around chronologically, which can be tough to follow, though the prose itself is full of emotion, vivid images and moments. Henderson said she originally had written the entire story from Jude’s perspective, though she changed that dramatically in the revisions to incorporate different perspectives, narratives and life experiences.

Henderson depicts a scary New York City -- especially the Alphabet City area -- painting the Lower East Side straight-edge scene of the late 1980s, including widespread drug abuse, the specter of AIDS and other issues. While she does a laudible job with setting and atmosphere, I do feel the entire punk-rock aspect of the novel felt forced, though it was obviously integral to the storyline.

“Fuck millionaires, fuck managers. This was 100 percent grassroots -- of the people, by the people, for the people. This was jump off a stage and know ten guys will catch you. This was fuck your dreams and make your destiny.”

There were certainly some memorable scenes described, including the subway laser tag scene, Jude tripping on ‘shrooms in a Buddhist temple, and the road-trip details and minutiae. [On a side note, I found it humorous that a minor character sustained multiple serious injuries after being jumped, yet was still given a football scholarship to Duke even while he was using a cane. Apparently, even in fiction writing, the Blue Devils are a punchline in football!]

In terms of character building, the novel could have been alternatively titled as “Jude’s Journey,” though the story expands to include more of Eliza as it goes along. I think the story suffers from relegating Eliza to the background a lot, turning her into a bit player, to which we have too scant access to her feelings and emotions.

“Around boys she was herself, she could relax; she had nothing to win but them ... She wasn’t young. She didn’t want to save anyone; she wasn’t in love with other people’s suffering. She wanted to be consumed by it, eaten alive.”

“She had wanted to make something happen; she had asked for heartbreak and she’d gotten it. And it was bigger than anything in her life. She wanted to forget Teddy, and she wanted something to remember him by.”

I also found Les to be hysterical, and personally, thought the story could have used a bit more of his influence, especially near the end ( “... whose religious training was the sum of one semester of biblical literature and thirty years of crossword puzzles.”). Additionally, the casual way that Johnny was accorded rock-star status was a little far-fetched and somewhat difficult to accept. Unfortunately, I found the characters to be mostly unlikeable, which I thought detracted somewhat from the ability to become fully immersed in the story.

Though a triangle of Johnny-Jude-Eliza is described, it is truly a quadrangle, with each vying to maintain or preserve a piece of Teddy. It’s also a story about interpersonal relationships, about how people can feel drawn and indebted to more than one person at a time -- not to mention the intricate webwork that describes how different people relate to each other -- and about how those feelings can lead to difficult choices. And sometimes those relationships are with idealized memories and wistful regrets instead of people. But I don’t think we’re ever privy enough to Johnny’s -- or Eliza’s -- true feelings, which makes it difficult to reinforce those worthwhile messages.

“The baby was already an angel, Teddy’s golden-winged redemption, and now maybe it would be Johnny’s, too.”

“Johnny felt the spirits of the city howling for his attention—not the dead but the waiting to die and the waiting to be born.”

“It was as though Johnny and Jude had been engaged in a staring contest, each daring the other to speak Teddy’s name first, and even thought it meant he would lose, Jude was desperate to blink.”

“They had both wanted to be the one who knew Teddy best, they had both been Teddy for each other, and now the make-believe had come to an end.”

A key character comes out of the closet halfway through the book, adding intrigue to a significant sexual dynamic in the tale -- with AIDS overhanging this vital plot turn. I also think Jude’s sexuality was questionable throughout much of the novel, until his dynamic with Eliza emerges (too late, in my opinion). When it finally comes to the surface, it is depicted beautifully, with the tentative, fumbling, nervous, fluttering feelings that those situations can evoke in the adolescents in all of us.

“‘It’s a nice face,’ she said.

“Nice. It was so much more than nice, but she couldn’t think of a better word. You didn’t call a boy beautiful, not a boy who was your husband’s best friend, not a boy who didn’t like girls and who went around picking fights and who you really did think was beautiful.”

“He deserved her, and Johnny didn’t. This had been his belief all along, but he had lived with his discontentment uneasily; he’d felt unentitled to it. Now his desire flamed up in him, fully formed, righteous; he held a ticket; he had the burden of proof ...”

“Kissing her had been like playing a song ... The kiss had steps, phases—a bridge, a chorus, an appetizer, something to cleanse the palate. It had a shape, a momentum ...”

Eventually, Jude leaves his abuses behind to embrace the clean lifestyle of straight edge, following in Johnny’s footsteps and becoming what Les describes as a “turbulent little reverend.” I had an issue with the transition of the group from the peaceful, keep-to-yourself straight-edge movement toward a violent clique bent on pressing their morality onto abusers. I felt Henderson mentioned this more in passing, with the thought process unexplained, and this transition, to me, was too significant to be handled so subtly. After all, when you’re discussing shooting drunks with BB guns, I don’t think there’s a lot of room to be subtle as an author.

“He didn’t want to be on the run anymore ... He wanted things to be the way they used to be ... He wanted to need no one.”

“Jude saw himself now for what he was: inessential. He was the tissue that bound the essential members together -- Teddy, Johnny, Eliza, those who were joined by blood or by sex. Jude was joined to no one by neither. He was beyond rescue.”

“He was jealous of everyone who knew how they wanted to be loved.”

The story regains its footing near the end, with a plot twist where Teddy’s father is found, he turns out to be a lawyer and is convinced to go after Eliza’s fitness as a mother. Considering how easy it becomes to forgot how young all the characters really are, it is refreshing when, at the end, we see that the are finally accorded some semblance of normalcy and a return to youth. As if some recognition that trading Teddy’s memory for Teddy’s offspring would never truly honor Teddy in the way they had so foolishly hoped.

“But what then to do with this immense relief, this joy rolling out like a carpet before him, the surprise gift of their youth returned to their hands?

“He wondered if his own birth mother, unburdened by him, went on to live her life and kiss boys.”

“ ... cradling the ashes awkwardly in his arms. They weighed perhaps as much as a newborn baby, and he looked down at them with the same terror and awe with which a new father might look at his child, holding it for the first time.”

Though many will be unhappy with all of the unanswered questions (what happened to Johnny -- did he die in San Francisco? Who was Jude’s unnamed wife -- was it Eliza? If not, what became of Eliza? How long did they stay in the straight-edge movement?), to me, the strong conclusion salvaged some earlier dragging parts of the tale.

All in all, I felt “Ten Thousand Saints” was a great tale, though not a great story. Being that that likely doesn’t make much sense, I’ll add that I felt there were a lot of clever and evocative elements in play, making for a more-than-worthwhile story to tell. However, I felt the plot drifted a bit too much, with too little sharing of how the main characters truly feel about each other.

Of course, I’ve pointed out what I see are some flaws. But to be fair, Henderson employs some really beautiful, mature writing, and eminently quotable turns of phrase. The result is an evocative, humorous novel, a coming-of-age tale wrapped in a series of love stories, fraught with real emotion ... balanced by harsh reality.

“ ... despite himself, the first thing he did was hunt for evidence of the baby’s genes, the science project -- blue and yellow make green -- at which no one in the history of the world has ever failed to be amazed.”