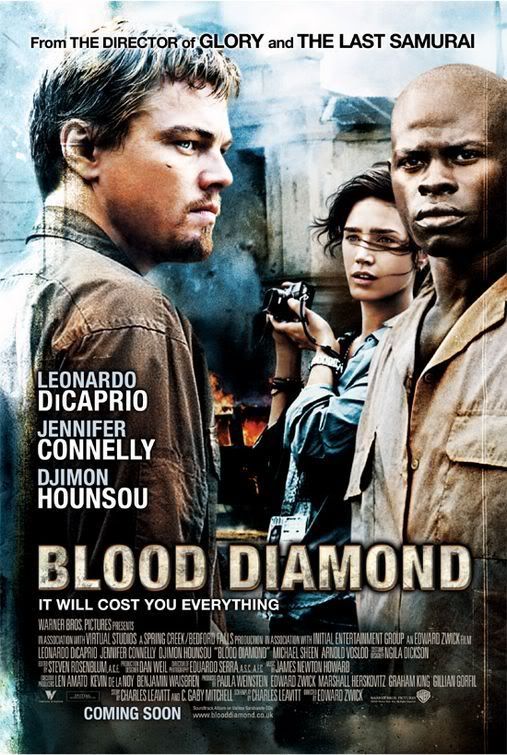

If you can get past Leonardo di Caprio’s painful British accident, “Blood Diamond” strikes a chord, resonating as “Last King of Scotland” on steroids. With intense combat scenes, heart-pounding drama and gruesome images that remind us of a reality not much different than the one depicted on the screen, this film makes you squirm less from the violence as from the idea that such actions and plotlines are likely taking place daily in that part of the world.

The Sierra Leone of a decade ago shines as an uncredited member of the cast, with striking beauty overridden by a bloody past and a future full of hopelessness. In this setting, Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou) endures his village being attacked and his family being taken away by the rebels, who enslave him instead of cutting off his arms. Vandy is put to work sifting through the river for diamonds, and he stumbles upon an enormous pink diamond. He is caught attempting to hide the diamond when the commandant of the rebel forces catches him, but just then, government forces attack, overrunning the rebel camp and giving Vandy time to bury the diamond. However, the commandant survives the assault, and when he is placed in the same jail as Vandy, he offers a huge reward to the others in the jail if they can find out where Vandy hid the priceless diamond. That’s when diCaprio comes on the scene as Danny Archer, an African-born smuggler. Placed in the same jail cell as Vandy, he overhears the talk of the rare diamond, which helps him hatch a plan to free Vandy and hunt down the prize.

Director Edward Zwick then introduces socially conscious journalist Maddy Bowen to serve as Archer’s conscience and love interest. In this role, Jennifer Connelly somehow pulls off the ever-so-rare feat of looking really hot even as she’s trudging through a jungle, bypassing showers and facing torture at the hands of crazed rebels. She challenges Archer’s motives, and when she is introduced to Vandy, she takes it upon herself to track down where Vandy’s family has been detained. When they finally find his wife and daughter, Vandy is told that his son, Dia, has been indoctrinated into the rebel army, taught to cast morality aside and kill and plunder without a second thought. With Archer forcing him to chase the diamond, Vandy only wants to find his son and rescue him from a meaningless life of blood-lust and certain death.

Vandy eventually finds his son, who has adopted the symbolic rebel name of See Me No More, but when he approaches him, he is not recognized as his father and is called a traitor, which lands him right back where he started—enslaved, face down in the river, looking for diamonds. He again falls under the rule of the commandant, who tells him, “You think I am the devil. But only because I have lived in hell. I want to get out. You will help me.”

Without giving away the ending, there are some wonderful touches down the stretch from Zwick, highlighted by a tremendous scene between father and son as Vandy attempts to hammer down the emotionless walls created by the rebels to break through to the child he once knew, before Dia pulls the trigger on Archer. The scene of the conference that displays Vandy’s role on the global stage in helping to raise awareness and curb the trading of conflict diamonds is also very powerful.

But there were certainly a few somewhat troublesome aspects of the flick. In such an enormous region, the sheer number of coincidences and just-at-the-nick-of-time occurrences are a little off-putting. Also, it seems to be a little much to think that a diamond company—Van de Kamp—would own an army and perpetrate such horrors in order to dominate the Sierra Leone diamond market, but then again, who knows in this world. Plus, Archer’s call to Bowen on the sat phone at the end feels a tad predictable, although it was probably necessary in the course of resolution.

And finally, Archer’s role as the mercenary with a heart of gold seems somewhat fabricated. Is the audience supposed to like him or not? The viewer is pulled in several directions in trying to determine Archer’s true character, which is useful in reflecting the uncertainty of the region, but head-scratching in the sense that there are enough emotions being played to in the movie without being reduced to confusion and ambivalence toward the dominant character. The idea that he can be vindicated so easily at the end (apparently), comes across as a trifle forced.

Yet at the end, it eventually becomes apparent that this is not a movie about diamonds; it is a film about T.I.A.: “This Is Africa.” A line repeated a few times within the flick, this sentiment seems to cover all that takes place in this continent borne and sustained of blood and violence. In its essence, “Blood Diamond” was actually about the heartlessness, destroyed lives, robbed childhoods and stolen souls involved in the creation of child soldiers who are forced to continue the horrific, traditional cycle of Africa.

Just prior to the credits rolling, the most revealing aspect of the movie comes across in the form of words: “There are still 200,000 child soldiers in Africa.” A short, simple, to-the-point sentence that says everything you need to know about “Blood Diamond.” This movie was very well-done and well worth checking out … but it narrowly missed the mark of its own point.

No comments:

Post a Comment